Simon de Montfort and All This Parliament Business

Imagine you are about to hear a community lecture marking the 750th anniversary of the founding of Parliament. You already know, whether from school or some story in the media, that it has something to do with Simon de Montfort. Perhaps he was the one who laid the cornerstone, made the opening address, coined the term Parliament. The speaker then appears and after some brief introductory remarks, gets right to the gist of it. ‘And this marked the first time that the burgesses were summoned to Parliament.’ At that point, you notice other people thinking the same thing you are: what and who are these burgesses? The speaker soon clarifies it by saying this was the first time the cities, like the counties before them, had representation in Parliament. Confusion thereafter gives way to disappointment. That’s it? All this hoopla over city people like Londoners being given the opportunity to throw their weight around?

If it seems like a letdown, and therefore another reason why there is no monument to Montfort outside Parliament today, the summoning of the burgesses was in fact a major step in the political development of the nation. It pointed the way towards a state free of the intricate patchwork of feudal loyalties. Historians, however, are not apt to see Montfort as any kind of visionary in this respect. He summoned the burgesses because he had lost the support of most of the baronage. But that’s precisely the point. The ancestral nobility of England was loath to give up the power and privileges that came their way through feudalism and were clearly not keen on sharing them with any emerging bourgeois class. Montfort did not leave behind a draft of his thoughts to indicate where he was intending to take Parliament in the long run, but we can chart the course that made the summoning of the burgesses merely the culmination of his efforts to make Parliament an independent body of government. These efforts went back exactly five years before his famous Parliament and would, in the end, cost him his life

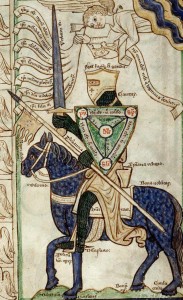

The word parliament was first used in official records in 1236, a new way of describing what was essentially an old institution. The Norman kings had always had their great councils; assemblies of the great men of the realm convened to discuss petitions and the business of the realm. French was the language of government, so there’s no telling who coined the term for these discussions. For all anyone knows, it might have been Montfort himself. He was one of King Henry III’s most trusted courtiers at the time, the younger son of a French noble family who had arrived in England several years earlier with the most tenuous of claims to the earldom of Leicester. His continental dialect, combined with a ‘courteous and pleasant way of speaking’, doubtlessly set him apart from the Anglo-Norman speaking members of the court. It certainly worked wonders on the king’s sister Eleanor, whom he would marry within two years

That marriage, conducted in secret by the king, would eventually create all kinds of resentment between Henry and Simon over the next twenty years. By the time the reform movement began, Henry’s resentment had turned into fear as the Montforts badgered him to no end over their private quarrels. The break finally came at the beginning of 1260, when Montfort left the king’s party in France, without even saying goodbye to Henry, and returned to England with a specific purpose in mind: to hold Parliament, with or without the king

This was indeed radical. Parliament, no matter what the form or name, had always been the king’s prerogative. The Provisions drawn up in Oxford in 1258 to reform the realm took that away from him, basically made Parliament a permanent institution of the state by stipulating it to meet three times a year at regular intervals. Henry had sworn to abide by the Provisions, and so far Parliament had met as required, but when a treaty with France took him across the Channel at the end of 1259, he saw his chance to undermine them and reclaim his prerogatives. Alleging one delay or another, he ordered Parliament not to meet until he returned, even if that meant missing the February deadline under the Provisions.

Montfort was having none of it and led a party to London, which included Henry’s son and heir Edward, to demand that the show go on. The magnates who had joined Simon in the original showdown with the king in 1258 were scared at the thought of outright defiance and chose to keep their heads down. In the end, Parliament was not held until the king returned in April. Montfort was not included on the list of people to invite, not to parliament anyway. Instead the king ordered him to stand trial for treason

Nothing came of the trial for a variety of reasons, but in the summer of 1261 Henry again united the reformers by asking and receiving papal absolution from his oath to the Provisions. Montfort took the lead in fighting back by deciding that Parliament would not only be held without the king’s authority, but without the king himself. ‘We don’t need him’ was more or less his attitude, but in fact he had turned to an innovation for Parliament that had come from the king himself.

Back in 1254, Henry was overseas in Gascony and in need of money. He asked his regents to convene Parliament and to specifically ask the sheriffs to have two knights elected for the purpose of representing their counties in the discussion for a tax. He was hoping to bypass his obstinate barons by appealing directly to the patriotic sentiments of the nation. Simon was present at that Parliament and no doubt left impressed with the political potential of this new constituency. And so it was to the knightly class that he turned for his ‘rogue’ Parliament of 1261, a move which so unnerved the king that he quickly sent his own summons to the knights, asking them to meet him instead. In the end, the knights too preferred to keep their heads down and went nowhere. In any event, the court by this time had bought off one of the leading reformers and the whole movement collapsed again. Fed up with all the cravenness around him, Montfort took his family and went to live in France

Had Henry’s court enjoyed sharper political acumen, they would have let things be and reform might have died of its own accord. But they insisted on pursuing vendettas at home and abroad, with the result that Simon returned in the spring of 1263 to lead a campaign that forced the king to accept the Provisions once again. The twists and turns eventually led to civil war and Montfort capturing Henry and Edward at the battle of Lewes. The son, his former ally but now implacable enemy, he locked away in Dover, and the king he took with him to London in preparation for a Parliament that in many ways was even more significant than the one held after it (those burgesses)

In the events before and after Lewes, most of the barons were on the king’s side, most of the clergy on Simon’s, and the knights were somewhere in between. Simon had that political acumen sorely lacking among the Henry’s men and knew he would need what knightly support he could muster if his radical new government was going to survive. In June 1264, with the entire royal family still in England under castle arrest, he summoned Parliament to meet and discuss what was called an Ordinance but in reality was nothing less than a constitutional monarchy. It embodied the Provisions around a two-tier system of conciliar control of the king and his family. It doesn’t really matter whether Montfort intended that control to be dictated by his party. What he’s doing is asking Parliament for their approval of his plan. Equally important, however, is that the knights in attendance didn’t come to merely rubberstamp his initiatives. They wanted something, too

Another of the king’s cherished prerogatives was the appointment of sheriffs. The abuses committed by these crown officials, mostly with orders from above, saw his authority there stripped away as well during the reform period. Henry’s determination to name his own sheriffs was understandably an even bigger flashpoint than Parliament was because it affected all members of the realm directly. Under the Provisions, now again the law of the land, the council would oversee the appointments. It was dominated by Montfortians, and since they wanted something from the knights, namely approval of their constitution, the knights wanted something from them, the right to appoint their own sheriffs. We don’t know how long this discussion was in committee or what trade-offs might have accompanied it, but each side in the end got what it wanted, and all the king could do was sit by and glumly look on

The importance of this assembly cannot be exaggerated. For the first time, a nationally elected assembly is meeting for the purpose of passing legislation worked out through compromise and after being proposed by the leader of the dominant party. It was an emergency session to be sure. The queen was busy preparing an invasion force on the continent and Edward’s friends in the Welsh marches had launched an insurgency in violation of the peace terms. Montfort literally had to be in three places at once, a gift he seems to have inherited from his father, but by the end of the summer he had beaten back the threats and made sure to embody the Ordinance in a final peace treaty which, interestingly, hinted that he expected the constitutional monarchy to continue into the next reign and beyond. Against this backdrop, summoning the burgesses for what turned out to be his last Parliament was merely the next logical step

So if all this talk about the towns getting their say in Parliament seems like a measly reason for celebrating any anniversary of it, it should be remembered that it was merely the tip of a long and costly struggle to make Parliament at least an equal partner in government. But it didn’t end with Montfort’s fall at Evesham. Edward was chastened by his year in captivity, where he presumably pondered his mistakes and reflected on the time when he joined his uncle five years previously in insisting that Parliament meet as stipulated by law. He knew there was no going back from as far as it had come, so when Parliament subsequently refused Henry a tax for Edward’s crusade, neither sulked off as Henry was wont to do before and resort to other methods of getting the money. Now they summoned it again, and again, and again, each time hammering out legislation that would appeal to the knights and their localities, mainly with regard to Jewish finance, which was an intolerable situation created in the first place by people like Henry, Edward and the rest of the court. They finally got their tax after two full years, but the message was clear for all time to come. Parliament held the purse strings, which is to say the ultimate power in the land, and the origins of that power can be traced back to the struggle that took place between Simon de Montfort and Henry III in the middle of thirteenth century.